Anyone who knows me knows that I love photography. This is probably why I am both a photographer and a printer.

Since I was a child I enjoyed making things. When I was around 15 or 16 I decided to get a camera as another means of creating. I had no idea at that time that photography would end up being one of the only consistent things in my life over the coming years.

Shortly after I began taking photos I also got interested in cameras themselves. Luckily I got into photography before digital cameras were readily available and so I got to learn completely on film. This also meant that it was rather easy to buy much older cameras and use them just as I would any other camera, film being more readily available at the time. By the time I was 19 I had some 215 cameras in my room on custom built shelves or spinning displays that I got from department stores that no longer needed them.

When I moved to Charleston at age 20 I unfortunately decided to part with the majority of my camera collection. Yeah, bad move. Still, I hung on to many of them because, in addition to photography, I also love design and there are some truly beautifully designed cameras out there.

It’s an interesting idea to me that a camera can not only create beautiful things but can also be a beautiful creation in itself; tools can be both functional and beautiful. A camera is the tool which photographers use to capture light, but can’t it be fun to use a beautiful one? With that in mind, here are what I consider to be some beautiful camera designs.

Polaroid SX-70

Polaroid SX-70 Camera

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- How To Open A Polaroid SX-70 Camera

- Polaroid SX-70 Camera Collapsed Closed

- Polaroid SX-70 Camera

- Polaroid SX-70 Camera Film Release

- Polaroid SX-70 Camera Opem

- Polaroid SX-70 Camera Viewfinder

The Polaroid SX-70 may well be my favorite camera ever made. Introduced in the early 1970s, the camera collapses down flat so that it can be stored quite easily, even in a large pocket, and then pops back up when you’re ready to take a photo.

Believe it or not, the SX-70 is actually an SLR, which means that when you look through the viewfinder you’re actually looking through the lens that takes the photo thanks to some fun mirror magic going on inside. When you take a photo a mirror moves out of the way inside and exposes the film and then returns to its original position. If this internal piece does not snap back into place properly it will prevent the camera from fully collapsing and has led many people to think their SX-70s are broken. However, putting a new pack of film with a new battery in the camera will correct the problem most of the time.

Speaking of the film, the camera took what was called SX-70 or Time Zero film. At the time of its introduction one of the amazing things about it was that the film developed quickly (relative to older Polaroid designs) and made no mess. Ironically, the film dried significantly slower than more modern Polaroid films, such as 600, and it was this extended drying time which led people to finding out that they could manually manipulate the emulsion inside the photo while it was still wet to produce a variety of interesting results. In fact, I have an entire series of work shot on a Polaroid SX-70 and hand manipulated. The film was discontinued in the early 2000s though you can still find film to fit the camera which is made by the Impossible Project. While the film does work in the camera (and being able to use such a beautiful camera again is fantastic in its own right!) my experience is that the new film does not have the characteristics of the original film and so doesn’t manipulate the same way.

There were several different SX-70 models produced, though my favorite remains the original metal-coated-plastic-with-brownish-fake-leather version.

Kodak Bantam Special

Kodak Bantam Special Camera On Built In Stand

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Kodak Bantam Special Camera

- Kodak Bantam Special Camera Closed

- Kodak Bantam Special Camera With Supermatic Shutter

- Two Kodak Bantam Special Camera Versions (Supermatic Left, Compur Right)

- Kodak Bantam Special Camera Back

- Kodak Bantam Special Camera Uses 828 Film

While the Polaroid SX-70 may be my favorite camera ever made, the Kodak Bantam Special is probably, in my opinion, the most beautiful camera ever made. Designed by Walter Dorwin Teague the Bantam Special is a truly beautiful example of Art Deco style.

The Bantam Special was unfortunately made for 828 film. I say unfortunately because 828 never really caught on, which means the film is hard to find, hard to process, and expensive. Kodak made 828 in hopes that they could make cameras that take this proprietary film and then people would have to buy more of their film. If these things accepted 35mm film I’d still shoot with one for fun today. 828 is the same width as 35mm, it just doesn’t have the same sprocket holes and it is paper backed (think 120 film) rather than being inside a cartridge. This means that 35mm can be re-spooled so you can still buy 828 film here and there.

There were a couple different versions of the Bantam Special with pre-war cameras having a German Compur shutter and subsequent models being made with a Supermatic shutter, which was American. The Bantam Specials with functional Supermatic shutters are often considered more valuable because there are less of them and the Supermatic shutters are often found to no longer be properly functioning. Interestingly, my Bantam Special with the Supermatic shutter works better than my other with the Compur shutter.

Since I’m talking about cameras for the sake of beauty here it’s worth mentioning that I aesthetically prefer the Supermatic version. Why? Because of the red paint indicating the slower shutter speeds, the “Kodak” name on the shutter cocking mechanism, and the design of the shutter speed ring. The red accent against the black and silver body puts the finishing touches on an already beautiful camera.

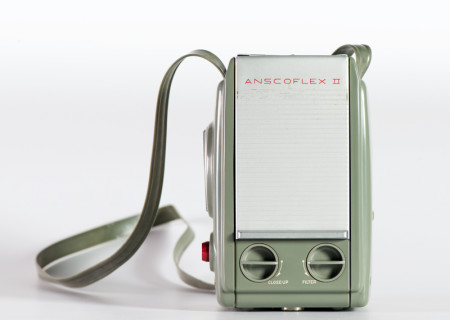

Anscoflex II

Anscoflex II Camera Front

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Anscoflex II Camera Open

- Anscoflex II Camera Front

- Anscoflex II Camera Closed

- Anscoflex II Camera with Flash

- Anscoflex II Camera With Flash

I’ve read where people have called this the “garage door”. If so, then I’d love to have a garage door like this.

Though it looks like a TLR (twin lens reflex) it actually isn’t as the lens is fixed, so there’s no focusing of the taking lens and nothing in the viewing lens to indicate focus. You simply point and shoot. It was made to shoot on 620 film.

Designed by Raymond Loewy (who also designed many other beautiful things) there were two models of this camera, the Anscoflex and the Anscoflex II. Design wise I prefer the II because of the addition of the two dials on the front of the camera. One dial is used for close up focusing and the other adds a yellow filter for black and white photography.

The sliding front serves two purposes. It reveals the lens for picture taking while also serving as the front part of the viewfinder hood, blocking light so that you can see through the viewfinder more clearly. Though not a particularly heavy camera it has a metal body.

While the sliding front is my favorite part I cannot help but point out that shiny red shutter button. It’s like an invitation to take photos (or at least push it repeatedly).

Penti II

Penti II Camera

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Penti II Camera Front

- Penti II Camera Back

- Penti II Camera Open

- Penti II Camera Top

The Penti II was made in Germany and is what’s known as a half-frame camera. It shoots on 35mm film (using its own special cartridges) though it takes photos only half of the size of a normal 35mm camera (have a look at the photo with the back removed to see what I mean). This also means that when you look through the viewfinder you see a naturally vertical image instead of the usual horizontal orientation of most cameras.

The Penti II has a metal body and to change the film you remove the entire back. One interesting feature of the Penti cameras is that they have a bar which sticks out of the side of the camera. This is the film advance lever. When you push this bar back into the camera it resets the shutter and advances the film to the next frame. Upon taking a photo the bar shoots back out the side.

You can still use these cameras though you will have to have the cartridges that go in the camera and load 35mm film into them. You may even be able to find one with a functional meter (the Penti II has a meter, the Penti I does not, even though it was designed to look like it does).

I have noticed that these cameras don’t seem to be quite as available in the US as they once were. Most of these I see listed on eBay are now coming from somewhere in Europe.

Yashica 44A

Yashica 44 A Camera

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Yashica 44 A Camera Front

- Yashica 44 A Camera Focus Knob

- Yashica 44 A Camera Film Advance

- Yashica 44 A Camera Back

- Yashica 44 A Camera Viewfinder

- Yashica 44 A Camera

The Yashica 44 is a true TLR, which stands for twin lens reflex, and it is a way of saying that there are two lenses, one which you look through, and one through which you photograph. Both lenses move together when you focus and you look through the top of the camera to see when you’ve gotten the focus correct. I will admit I have a bias when it comes to TLRs because I find them to be generally beautiful. In fact, just about any Rolleiflex you find will likely be a beautiful camera (and on that note, the Yashica 44 is quite likely a copy of the baby Rolleiflex).

The Yashica 44 is a Japanese made camera that came in three versions: 44, 44A, and 44LM.

The 44LM has an external light meter and an “LM” badge added and was geared towards a more advanced photographer.

The 44A was made to be a simpler version of the 44. Visually, for me, the difference lies completely in the name plate and top lens area, which is the lens you look through. I love the simpler, less bulky lens with the vertical, contrasting strips of leatherette on either side of it. It makes the camera look clean and straightforward. And I love the metal “Yashica-44” nameplate with the 8 small vertical lines just under it.

Being a smaller camera it was made for 127 film, which you can still find with a quick Google search.

Polaroid Highlander (80, 80A, 80B)

Polaroid Model 80B Camera

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Polaroid Model 80B Camera Lens

- Polaroid Model 80B Camera Front Cover Details

- Polaroid Model 80B Camera

- Polaroid Model 80B Camera Open

- Polaroid Model 80B Camera Front Detail

- Polaroid Model 80B Camera Closed

And we’re back to Polaroid. Truth be told I like the look of a lot of Polaroid cameras, but this will be the last one that shows up in this list.

The Highlander was made in 3 models, the 80, 80A, and 80B. It just so happens that I have the 80B, but aesthetically I like the 80A just as much. I prefer the 80A and B to the regular 80 because the A and B are brown, whereas the 80 is gray.

Introduced in the 1950s, these cameras were a good bit smaller than the previous Polaroids. I have several earlier models and those things were big and heavy. Of course, the 80 is certainly not a light camera, but relatively speaking it was a definite improvement.

Aesthetically, my favorite part of these cameras is the very front area around the lens. I find the polished metal, horizontal lines, and curving edges just past the red “Polaroid” script to be beautiful.

Though most people know polaroid for their packs of film, the 80 models took a type of roll film in the 30 series, which isn’t made anymore. I have read that these can be converted to take certain types of pack film, though I’ve never tried that myself.

Voigtlander Vitessa L

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Voigtlander Vitessa L Camera Open

- Voigtlander Vitessa L Camera Front

- Voigtlander Vitessa L Camera Ultron Lens

- Voigtlander Vitessa L Camera Top

- Voigtlander Vitessa L Camera Back

- Voigtlander Vitessa L Camera Back Removed

The Voigtlander Vitessa is what is sometimes called a 35mm folding rangefinder. This simply means it shoots 35mm film, the lens folds away, and it is a rangefinder as opposed to an SLR. This style was popular for a while and many companies made various models that are of the same style, some of the more popular ones being the Kodak Retina and the Zeiss Contina. They made several versions of the Vitessa, and my particular one is the Vitessa L, which has a light meter.

The Voigtlander has several unique features, which some may think are better described as quirks, that make me particularly like it.

First, the door on the front doesn’t open on one side with a hinge on the other like most folding cameras. This one has two doors that open in the center. I’ve read where people call them “barn doors”. To close the camera you push on the lens where the two red markers are.

Second, like the Penti mentioned above, it has a plunger on the top which, when depressed, resets the shutter and advances the film. While this can be awkward it also has some advantages. Most cameras requiring you to manually advance the film use a lever that is on or near the shutter release button. This means you have to take the camera away from your eye to advance the film. With the Vitessa’s plunger you can advance the film with your left hand all while never moving your finger from the shutter button or taking the camera away from your eye.

Third, to focus the Vitessa you use the wheel on the back of the camera. By sliding your thumb left or right it moves the lens in the front in order to focus. The scale for focus distance isn’t on the lens either, it is on a wheel on top of the camera that spins as you rotate the wheel on the back.

On top of that it has a fantastic Ultron lens that is widely regarded as being incredibly sharp. Since it uses 35mm film you can still readily use these cameras today.

Add all these things together and you have a unique, innovative camera surprisingly from the 1950s.

Kodak Duaflex II

Kodak Duaflex II Camera With Flash

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Kodak Duaflex II Camera Front

- Kodak Duaflex II Camera Shutter Release Side

- Kodak Duaflex II Camera Back With Flash

The Duaflex line of cameras were made in the late 1940s through the 1950s. Like the Anscoflex II above they are also not true TLRs, though they do have two lenses.

Many versions of the Duaflex were made from the original Duaflex through the Duaflex IV. They were all made for 620 film. One interesting thing is that you can find various models with the same model number on them that look different from one another. For example, my personal favorite is the Duaflex II pictured here. However, not all Duaflex IIs look this way. Some have different lenses and don’t have the aperture setting just below it. I don’t really know how many variations of each version were made (it would be fun to figure that out), but they are inexpensive and readily available to buy today as there were lots of them made.

Ihagee Exa / Exacta

Ihagee Exa Camera

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Ihagee Exa Camera Front

- Ihagee Exa Camera With Finder

- Ihagee Exa Camera Removable Lens

- Ihagee Exa Back

- Ihagee Exa Camera Takes 35mm Film

- Ihagee Exa Waist Level Finder

Another German camera, the Exa was made by a company called Ihagee, located in the city of Dresden. Ihagee made a line of camera called Exacta also.

My understanding is that the Exa cameras were made as a simpler version of the Exacta, though I can tell you it is quite well made. Mine is still fully functional. It takes 35mm film also so that makes it even better as it can still be readily used. It has quite limited shutter speeds however, topping out at 1/125 sec.

One of my favorite things about these cameras is the waist level finder option. You can use it looking down or open the front flap to look straight through. Though not incredibly versatile, it at least looks nice.

Various lenses are available for the Exa/Exactas and neither they nor the bodies are particularly expensive to buy.

Kodak Brownie Hawkeye

- Brownie Hawkeye Flash Camera Front

- Brownie Hawkeye Flash Camera Back

- Brownie Hawkeye Flash Camera Open

- Brownie Hawkeye Flash Camera With Flash

This, in my opinion, is one of the classic camera designs. They are cheap, abundant, and are easily recognized. In fact, you may have already seen this camera before as it was one of the most popular Brownie cameras ever produced. Because they were so affordable they were popular, and thus there are tons of them out there. They are readily available and you can buy them for often $10 or less.

With versions made both with a flash and without a flash, it doesn’t get much simpler than this as far as cameras go. There’s nothing to focus, no special viewfinder, and nothing else to set.

These cameras were made to fit 620 film. I have read conflicting reports that you can use 120 film in some of them. Apparently there was a time when they would fit 120 spools, but then the manufacturing was changed so others won’t take 120. You will simply have to find one and see if you get lucky. If so, then you can use it with currently produced 120 film. Otherwise you’ll have to buy 620 that has been re-spooled from 120 film. You can find it, it’s just more expensive.

Leica M6

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Leica M6 Camera Front

- Leica M6 Camera Back

- Leica M6 Camera Top

- Leica M6 Camera

- Leica M6 Camera Lens Collapsed

- Leica M6 Camera

Admittedly, I find just about anything designed by Leica to be beautiful. Even better, they make, and have made, some of the best made products you can buy.

Leica rangefinders have a rich history. Their cameras are practically responsible for making 35mm film so popular. The list of photographers who shoot or have shot Leica rangefinders is long and impressive, with perhaps Henri Cartier-Bresson sitting atop that list.

The Leica M series cameras are well built, beautiful, portable, and nearly silent. This helped them to become the most popular cameras for photojournalists as they could go anywhere, stand up to almost anything, and remain unobtrusive. Not too long ago I watched a documentary on modern NYC street photographers. I think all but one of those photographers had Leica Ms in their hands.

In specific, the M6 may well be my favorite of all the Leicas. The M6 represented a redesign from the previous M5 and gave the camera a clean, more modern look, yet it remained timeless. The M6 is fully mechanical, which means that it will function without batteries. Some of the cameras which came after the M6 require batteries to function. Also, the M6 has a very simple, straightforward light meter built in. That of course does require batteries, but the camera shoots whether the meter works or not. So for me it is the best of both worlds, a fully mechanical camera with the addition of a light meter, which the previous models did not have actually built into the camera.

Vest Pocket Kodak Autographic

Vest Pocket Kodak Autographic Camera

CLICK TO ENLARGE

- Vest Pocket Kodak Autographic Camera Front View

- Vest Pocket Kodak Autographic Camera Back With Opening For Writing

- Vest Pocket Kodak Autographic Shutter Detail

- Vest Pocket Kodak Autographic Camera Side View

- Vest Pocket Kodak Autographic Camera Open

- Vest Pocket Kodak Autographic Camera Back With Stylus

Vest Pocket is a fitting name as this camera can very easily be collapsed and slipped into a pocket. Kodak made more collapsing cameras with bellows than I could ever keep up with, but for some reason this little one has always been among my favorites.

It’s quite old; notice the most recent patent date of 1913 above the lens. These cameras were made in the late 19 teens and early 20s. The bellows are still light tight and it opens and closes easily. The areas painted black are made of brass and you can see the brass of mine showing through from years of wear. While not a camera in pristine shape, I like this brassing. It gives it a sort of “soul”.

One particularly interesting feature of this camera is its “autographic” aspect. On the back of the camera is a small door that opens. The doors has a spot where a small stylus slides into place. By opening the door and using the stylus you could sign your autograph, or write whatever you like really, onto the paper backing of its 127 film.

I’ve read several places that this camera was often called the soldier’s camera. Thanks to its popularity with soldiers there were many of these sold, which means there are quite a lot of them still around and available today.

There are more beautiful cameras out there than I could ever post about, but these are among my favorites. Perhaps in the future I will post about more. In the meantime, here’s a great camera collection that should keep you busy for a while.